TL;DR: Key Takeaways

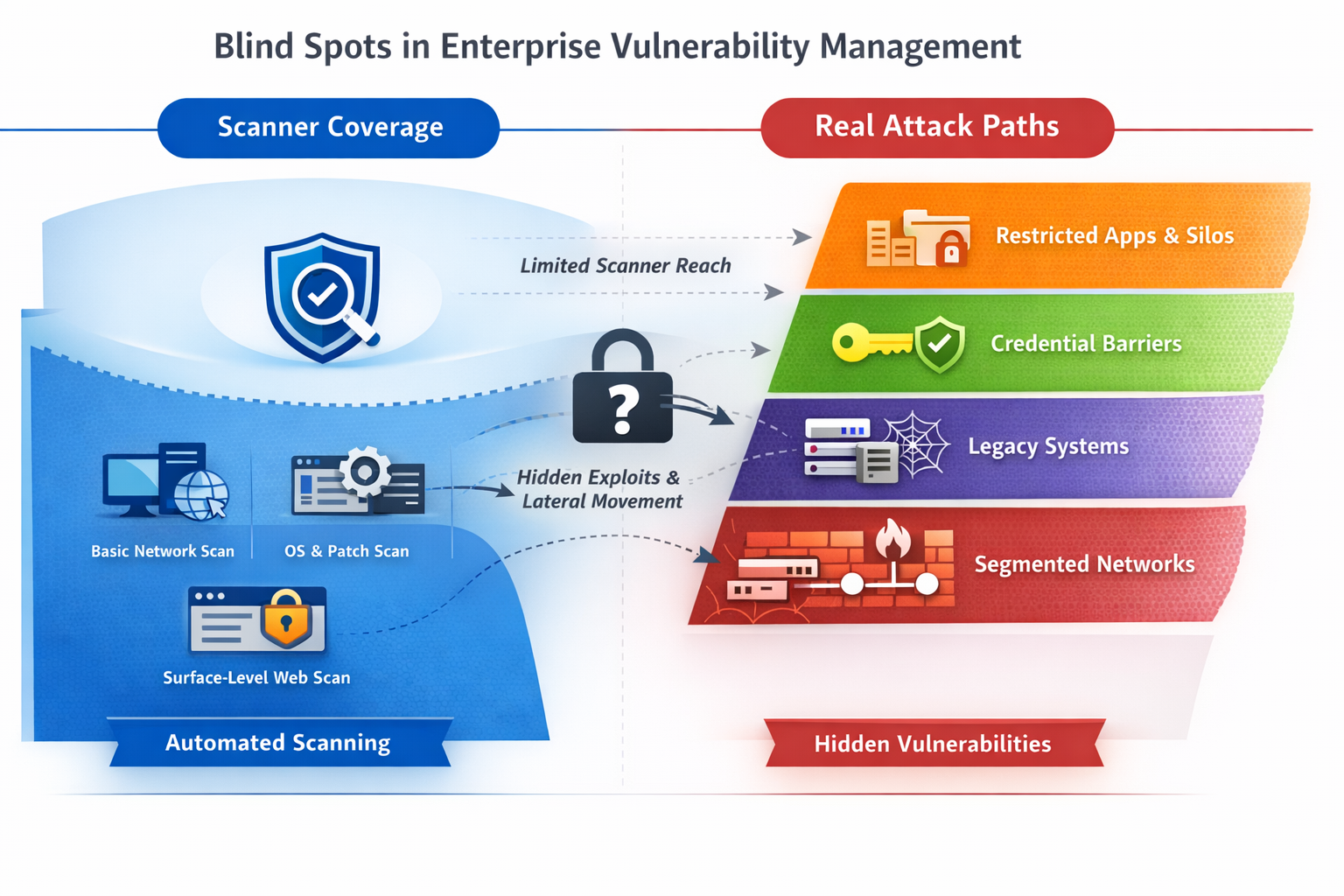

- Vulnerability scanners are essential for baseline hygiene, but structurally limited in depth, scope, and context.

- In large enterprises, especially in regulated Hong Kong sectors, organizational realities amplify these blind spots.

- “Clean” scan reports often mask real, exploitable attack paths inside segmented and credential-restricted environments.

- Use scanners for coverage and compliance — but treat red team validation as the reality check for what actually gets exploited.

CISOs, IT Risk leaders, Heads of Infrastructure, and executives in Hong Kong enterprises who rely on vulnerability scanning as a primary assurance mechanism.

In today’s large enterprise environments, vulnerability scanning forms the backbone of many cybersecurity programs. Automated tools continuously scan networks, applications, and infrastructure, feeding findings into risk registers, patch cycles, and compliance dashboards. The value proposition is clear: scanning is scalable, repeatable, and relatively low-cost compared to manual testing.

Yet despite widespread adoption — even within mature security organizations — critical gaps routinely persist. Red team assessments and post-incident investigations repeatedly uncover compromise paths that scanners classified as “clean” or low risk.

Across dozens of enterprise red team engagements over multiple years in regulated Hong Kong sectors — including financial services, telecom, and large conglomerates — we have observed the same pattern: scanner dashboards look reassuring, while meaningful attack paths remain hidden in internal layers the tools never reached.

“In one assessment, automated scans reported zero critical findings across internal web applications. Manual testing uncovered a SQL injection vulnerability that, when chained with other weaknesses, led to domain-level compromise. The scanner never accessed the vulnerable endpoint.”

Section 1 — Credentialed vs. Non-Credentialed Scanning: The Depth Gap

Executive takeaway: This is why “credentialed scanning” in dashboards often overstates real coverage.

The most fundamental limitation of vulnerability scanning lies in its authentication model.

Most organizations begin with non-credentialed (unauthenticated) scans because they are operationally simple. The scanner behaves like an external attacker, probing exposed services, ports, and unauthenticated endpoints. This is useful for identifying surface-level issues — but it only scratches the perimeter.

The majority of enterprise risk lives behind authentication. Business logic flaws, privilege escalation paths, internal APIs, and application-specific vulnerabilities are invisible to unauthenticated scans.

To compensate, organizations enable credentialed (authenticated) scanning. In practice, this introduces new failure modes. Managing credentials at scale is complex. Scanners struggle with Kerberos, OAuth, federated identity, MFA-protected applications, and session persistence. Credentials expire, are scoped narrowly, or are restricted to infrastructure layers rather than business-critical systems.

In zero-trust or segmented environments, credentials valid in one zone frequently fail in another. As a result, many “credentialed” scans still operate with privileges far below what attackers achieve after initial access.

Highlight: Common Credential Pitfalls

- Limited support for MFA-protected or federated authentication flows

- Credential scope restricted to infrastructure, excluding line-of-business applications

- Silent authentication failures that still produce “clean” results

In one regional financial services organization, scanner credentials accessed core servers but excluded finance and HR applications. Scan results showed no critical findings. Manual testing later uncovered exploitable flaws inside those restricted systems — exactly where attackers pivot after initial compromise.

Section 2 — Scope Blind Spots: Where Attackers Live but Scanners Don’t

Executive takeaway: This is where attackers operate between your segments and collaboration tools — places scanners rarely see.

Enterprise scan scope is almost never complete.

Collaboration platforms such as SharePoint, OneDrive, and Microsoft Teams are frequent blind spots. These platforms host sensitive documents, custom workflows, and embedded applications. Scanners may detect the portal but rarely authenticate deeply enough to test document libraries, Power Automate flows, or custom components.

Network segmentation further reduces visibility. Crown-jewel systems are deliberately isolated behind internal firewalls, reverse proxies, or hostname-based routing. Scanners placed in one segment cannot reach others without explicit access that is often intentionally denied.

Legacy and third-party applications compound the issue. Custom logic, proprietary integrations, and systems inherited through acquisitions routinely fall outside automated coverage. Ephemeral assets — containers or serverless functions — may not exist during scheduled scan windows at all.

These “out-of-scope” systems are rarely edge cases. They frequently form the backbone of real enterprise attack paths.

In one long-established telecom organization, a finance application inside a segmented network was excluded from scanning due to access constraints. A minor configuration weakness in that environment was later chained into a high-impact compromise during manual testing.

Highlight: Commonly Overlooked Assets

- Collaboration platforms with custom workflows

- Legacy applications from historical acquisitions

- Ephemeral cloud resources outside scan windows

Section 3 — Assumption Failures: When Scanners Trust the Environment Too Much

Executive takeaway: Clean reports often reflect broken assumptions, not real security.

Vulnerability scanners operate under assumptions that rarely hold in mature enterprise environments.

First, scanners assume reachability. If a service responds, the scanner expects meaningful interaction. In reality, WAFs, IPS devices, and rate limiting often block scanner payloads while allowing attacker-tuned traffic. The scanner records a false negative, not a blocked test.

Second, scanners assume uniform configuration. Version-based detection misses non-standard deployments, custom hardening, and environment-specific behavior that materially affects security posture.

Finally, scanners do not reason about attack chains. They detect isolated issues but fail to show how multiple low-severity weaknesses combine into material compromise — precisely how real attackers operate.

The result is a dangerous illusion of security: dashboards look clean while attack paths remain intact.

Section 4 — Organizational Realities: Why These Gaps Persist

Executive takeaway: This is not a tooling problem — it is an enterprise governance problem.

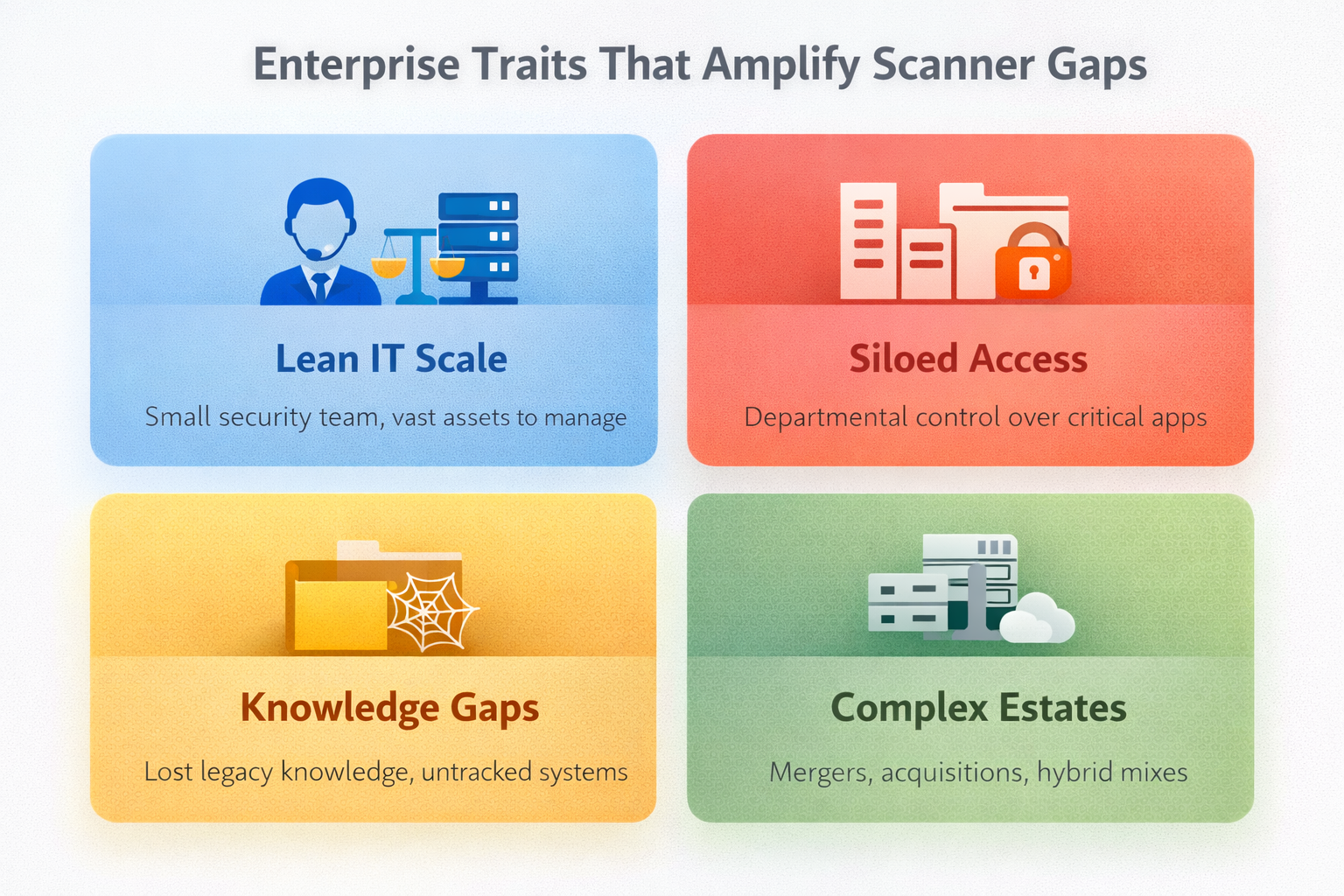

In large enterprises, scanner limitations are amplified by organizational realities.

Security teams operate as cost centers, with constrained headcount and growing asset inventories. New staff inherit infrastructure they did not design, with incomplete documentation and lost institutional knowledge.

Departmental silos further restrict visibility. Systems handling payroll, finance, legal, or HR data are owned by business units. Granting security teams broad access raises compliance concerns — particularly under PDPO — and business owners are cautious by necessity.

The outcome is systemic: scanners cannot reach critical assets, and security teams lack the authority or bandwidth to compensate manually.